My week on referral medicine turned out to be as advertised: busy, complicated patients, extra reading, and lots of cool procedures. I alternated between "I am so gonna specialise in internal medicine" and "OMG I just want to be a GP this is too stressful."

Since other groups have purportedly had difficulties with people hogging cases and whatnot, my group learned from their mistakes and picked names randomly to form the order that we would take cases. My name got drawn first, so I took the patient that came in on monday: a four-year-old dog, J. The notes said regurgitation and evidence of megaoesophagus on radiographs - cool, I find oesophageal disease very interesting.

He did not come in with a presentation of oesophageal disease. He was, in fact, making a horrible inspiratory respiratory noise that sounded pretty much exactly like laryngeal paralysis. For some reason, the owner wasn't particularly concerned about this fact, and was a lot more worried about the ongoing "vomiting" the dog had been having since his stay in the kennel. This also happened to be my

observed consult which made the whole scenario extra awkward. I proceeded with the consult as normal, but needless to say, we got the dog into the back and on oxygen pretty quickly.

So day 1 was all about stabilising him and figuring out what was going on. We got him into the O2 cage, got a catheter in (with difficulty), and gave him puffs from an inhaler just like people use. We planned to transfer him to surgery, and got him down to anaesthesia to have a laryngeal exam under sedation before they went ahead with the treatment (a laryngeal tie-back).

... He didn't have laryngeal paralysis. His larynx was fine.

Time for a new diagnosis, doctor. It's not like there are a thousand options on the differential diagnosis list... Also, we repeated the radiographs, and did indeed find megaoesophagus. Could it really be myasthenia gravis, the autoimmune disease that attacks the neuromuscular junction?

So J went for a neuro exam, with the boarded veterinary neurologist. She is

very good at what she does. She can break down this really complicated subject into something very understandable and her methodical, logical approach to a diagnosis is mind-blowing. Unfortunately, the neuro exam ended up with a really long list of bizarre and subtle symptoms, like short steps, droopy eyes, uneven pupils, and difficulty swallowing. We went over every possible nerve involved and decided it must be a neuropathy or myopathy of some kind, and dysautonomia was a possibility (screwy autonomic nervous system). Putting everything together, myasthenia gravis was still at the top of the list.

There is a really cool test you can do for MG, where you inject a drug and, if they have the disease, they magically get better. Like, instantly. It wears off after a few minutes, but then you know they just need the longer-acting form of that drug and they're good to go. The downside is that an overdose of the drug causes a spectacular crisis. So we tried this--cautiously--even though J's presentation was really weird. And guess what! They decided that he did, indeed, improve--his gait got better and his swallowing improved. Thus he got put onto neostygmine.

All seemed to be going well. Then, when I arrived the next morning, it turns out he ended up having a cholinergic crisis a few hours prior--the whole works: excitement, urination, defaecation, salivation, and all that. Very spectacular and stressful, especially because he pulled out his IV catheter and that made it hard to get the emergency drugs into him. So we fiddled with his dose, and he kept having crises. We switched him from IV drugs to oral drugs (they're absorbed more slwoly), and he kept having crises. Long story short, he didn't respond well to the drugs. His disease symptoms would improve dramatically, but a few hours after the meds he would just have another crisis. He also kept regurgitating, more and more as time went on, and after a while it become yellow, opaque, pus-like gunk. Not good.

At one point, we wanted to use fluoroscopy to identify the best consistency of food for his megaoesophagus. Feeding is a big ordeal because you don't want them to regurgitate it immediately and then inhale it, leading to aspitation pneumonia. The radiology crew got all excited, brought out the fluoroscope, lots of vets, a mob of students, everyone in their lead-lined gowns and all the imaging equipment set up... and J was very stressed out. He got stressed out even with small amounts of handling, so between so many people, and having to put him up onto the imaging table, he went into considerable respiratory distress again. So... "Sorry guys." Everyone dis-gowned and filed out. The radiology crew were very much "Oh no it's perfectly okay!" but I think the students were disappointed, because the fluoroscope isn't used often (it's like real-time x-ray).

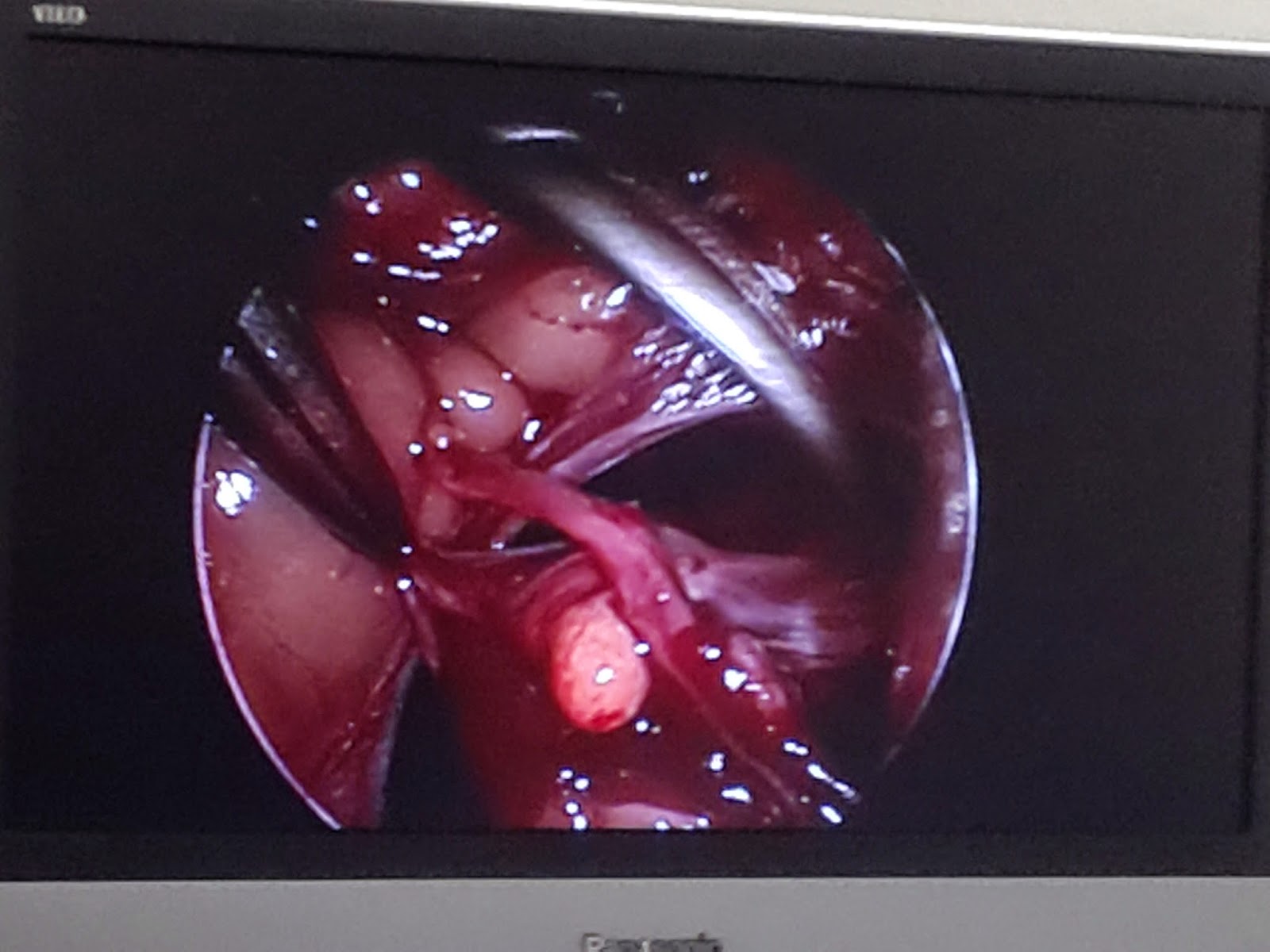

The neurologist suggested we try electroacupuncture. It doesn't perform miracles, but it's an effective adjunctive treatment with proven science. And it's

awesome. She had just got the gadget so it was her second EAP ever (she does normal acupuncture as well, it's just the electro part that was new, I believe). Using anatomical landmarks such as counting vertebrae, she placed these very very tiny needles into the skin, and connected them to lightweight wires. Even the needles alone were enough to cause endorphin release, and our agitated, nervous dog zonked out completely. When she turned on the current, it was total nap-time for him. It was performed in a quiet consult room.

The way the EAP works is basically using a reflex arc. It stimulates the dermatomes that connect to the spinal cord segments of interest. The signals go in, excite the spinal cord, and in turn signals go out to other muscles. In this case, it was to the oesophagus. The increased electrical activity stimulates the muscles to contract, which they aren't doing normally because of the disease. Then, hopefully, the contraction stimulated by EAP allows the body to regain some of its own, natural tone. She had no idea how effective it would be. However, in her previous patient, an arthritic dog, the EAP proved to be an amazing analgesic, and that dog was able to get up and run and jump almost like normal for a while after the EAP had been performed.

On the thursday, poor J was still having all those troubles with his meds. He'd had 2 sessions of EAP, we'd fiddled with his dose a ton, and he'd still been having regular crises. Then we noticed he was coughing and regurgitating purulent material, took more radiographs, and discovered what we had feared all week: he had aspirated and now had pneumonia. It's possible it had been brewing before he even arrived. It's possible he aspirated some of his food or water while in the hospital, since it's so difficult to manage a patient with megaoesopahgus, and he'd been regurgitating so much. But either way, it became a serious, intensive care situation. Back into the O2 cage, regular monitoring, three or four different IV antibiotics, and a plethora of nursing care requirements. That day was a holiday and I was only scheduled to come in for morning treatments (usually an hour at most), but I ended up there for 5 hours, between taking xrays, writing up the new patient management sheet/requirements, drawing up drugs, monitoring, and administering everything.

This would quickly turn into an extremely expensive, long-term ordeal. We were fairly confident we could get him through this bout of pneumonia, but the problem was that he was very likely to simply aspirate again. The megaoesophagus was likely to be a lifelong management issue, and he was not tolerating his drugs even at low doses. So on the friday, the owners elected to euthanise him. He has been sent to post-mortem to confirm our diagnosis, but I don't know the results of that. It was very sad because he had a dedicated owner, and we had all worked so hard.

Because it was such an interesting, unique, and complex case, this will be my presentation for Grand Rounds this year. There was a great deal of learning for a great deal of students, I got the opportunity to be hugely involved in the patient care, and it was a rare opportunity to see the tests and procedures involved with this rare disease. All in all, it was a great case to have, and I think my week on referral medicine gave a great taste of the many facets of internal medicine.