Assignment Checklist:

Poisonous plants project turned in.

4 person group project about handling a disaster turned in (we picked earthquake).

2 person group assignment about practice management turned in.

Last case report finished. (4 production, 2 equine)

Small animal disease client information handout finished.

Veterinary code of conduct assignment done.

Personality test assignment done (yes, they really made us do that).

4 person meatworks assignment out of the way.

Peer review of other groups' meatworks assignment finished.

Small animal surgical report, discharge instructions, anaesthetic record, and SOAP all signed off.

Red book skills 95% signed off.

Grand Rounds case presented to the department and done forever.

To do:

Public health case report.

Study for boards.

There is light at the end of the tunnel!

Sunday, 31 August 2014

Thursday, 28 August 2014

Refergency Friday and the Horse With Haemorrhagic Colitis

Warning: Blood is involved.

I once heard an internal medicine resident call Fridays "Refergency Friday," because it always seems that everyone waits until then to send over all the critical, complicated, or difficult cases. Today supported this trend, when the only emergency in all of equine roster rocked up at 9am. Not only was it an emergency, it was a potentially infectious (and potentially zoonotic) disease and the horse had to go straight into isolation.

Isolation is this little barn separated from the main equine barn. To go in, you have to put on special overalls and special boots, walk through disinfectants, and it's not a bad idea to put on two pairs of gloves. There are certain criteria for whether or not to put a horse in isolation:

2/3 of the following:

1. Fever

2. Diarrhoea

3. Low white blood cells

In our particular instance, we didn't find out that the horse had those things until it actually showed up. This was a prelude to the recurring theme of the fact that the history changed pretty much every single time someone talked to the client. However, the more immediate problem is that there are no supplies in isolation already; you have to bring everything down ahead of time, once you get the call. This makes sense because if the whole point is preventing spread of disease, you don't want to be using anything left over from the last patient that was in isolation.

So this nearly dead horse shows up and goes into isolation, and everyone starts moving at a frenetic pace. Unfortunately, about half the time when someone would ask me for something, I'd look around for it and find nothing. They wanted to put in an IV catheter, but the horse had terrible blood pressure, making it super difficult. Add this to the fact that I didn't have any of the things they actually needed and other students had to keep running back to the main barn to get them, tension got pretty high. Also, since we're students and not only didn't know our way around isolation (since we'd never been there before), the other student and I are totally not horse people and don't even know the basics. If someone asked for a certain object, we wouldn't know what it looked like, or which of several options they wanted. To top everything off, the horse was quite anxious, and it became dangerous on top of difficult to get anything done.

After a tense half an hour to an hour, the horse was finally sedated, catheterised, fluids were running, and things were more under control. Blood and abdominal fluid were sent off to the lab, and there was some time to catch our breath. After some teaching/learning about the physical exam findings and differential diagnoses, I got the lovely job of standing at the rear end with a pottle, waiting to catch what came out so someone could run diagnostics. This poor horse was literally crapping blood. Pure blood.

Things were looking pretty grim. Lab results kept making the picture worse and worse. The horse most likely had dead colon, allowing bacteria to translocate into the bloodstream and cause septicaemia, as well as fluid to collect in the abdomen. Blood was just pouring out the back end. Bloodwork showed that the kidney was showing signs of dysfunction, too. And though it was never confirmed, it was pretty likely that the horse was in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

They gave the horse some blood plasma, since when you're in a state like that, fluids aren't going to be enough. However, he had some sort of reaction (maybe anaphylaxis, or maybe he was just circling the drain and it was his time), and started getting wobbly, anxious, and then thrashing around. I wasn't there when this happened, but he came this close to killing someone. It was a downhill spiral from there, and he was euthanised.

He was sent over to post-mortem immediately, and we went down to have a look. His entire small and large colon was dead, dark and necrotic and haemorrhagic. The gut contents were mostly blood. It must have been a horrible, painful way to die. From the history, we suspected untreated intestinal parasites as a cause, though some other options include Salmonella, Clostridia, idiopathic colitis, or drug-induced. It's amazing to think that those things could cause such a horrific colitis.

I once heard an internal medicine resident call Fridays "Refergency Friday," because it always seems that everyone waits until then to send over all the critical, complicated, or difficult cases. Today supported this trend, when the only emergency in all of equine roster rocked up at 9am. Not only was it an emergency, it was a potentially infectious (and potentially zoonotic) disease and the horse had to go straight into isolation.

Isolation is this little barn separated from the main equine barn. To go in, you have to put on special overalls and special boots, walk through disinfectants, and it's not a bad idea to put on two pairs of gloves. There are certain criteria for whether or not to put a horse in isolation:

2/3 of the following:

1. Fever

2. Diarrhoea

3. Low white blood cells

In our particular instance, we didn't find out that the horse had those things until it actually showed up. This was a prelude to the recurring theme of the fact that the history changed pretty much every single time someone talked to the client. However, the more immediate problem is that there are no supplies in isolation already; you have to bring everything down ahead of time, once you get the call. This makes sense because if the whole point is preventing spread of disease, you don't want to be using anything left over from the last patient that was in isolation.

So this nearly dead horse shows up and goes into isolation, and everyone starts moving at a frenetic pace. Unfortunately, about half the time when someone would ask me for something, I'd look around for it and find nothing. They wanted to put in an IV catheter, but the horse had terrible blood pressure, making it super difficult. Add this to the fact that I didn't have any of the things they actually needed and other students had to keep running back to the main barn to get them, tension got pretty high. Also, since we're students and not only didn't know our way around isolation (since we'd never been there before), the other student and I are totally not horse people and don't even know the basics. If someone asked for a certain object, we wouldn't know what it looked like, or which of several options they wanted. To top everything off, the horse was quite anxious, and it became dangerous on top of difficult to get anything done.

After a tense half an hour to an hour, the horse was finally sedated, catheterised, fluids were running, and things were more under control. Blood and abdominal fluid were sent off to the lab, and there was some time to catch our breath. After some teaching/learning about the physical exam findings and differential diagnoses, I got the lovely job of standing at the rear end with a pottle, waiting to catch what came out so someone could run diagnostics. This poor horse was literally crapping blood. Pure blood.

Things were looking pretty grim. Lab results kept making the picture worse and worse. The horse most likely had dead colon, allowing bacteria to translocate into the bloodstream and cause septicaemia, as well as fluid to collect in the abdomen. Blood was just pouring out the back end. Bloodwork showed that the kidney was showing signs of dysfunction, too. And though it was never confirmed, it was pretty likely that the horse was in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

They gave the horse some blood plasma, since when you're in a state like that, fluids aren't going to be enough. However, he had some sort of reaction (maybe anaphylaxis, or maybe he was just circling the drain and it was his time), and started getting wobbly, anxious, and then thrashing around. I wasn't there when this happened, but he came this close to killing someone. It was a downhill spiral from there, and he was euthanised.

He was sent over to post-mortem immediately, and we went down to have a look. His entire small and large colon was dead, dark and necrotic and haemorrhagic. The gut contents were mostly blood. It must have been a horrible, painful way to die. From the history, we suspected untreated intestinal parasites as a cause, though some other options include Salmonella, Clostridia, idiopathic colitis, or drug-induced. It's amazing to think that those things could cause such a horrific colitis.

Wednesday, 27 August 2014

I Volunteered For A Complicated Case On The First Day Of Equine

I have mentioned before that I'm not the biggest fan of horses. I am so not a fan of horses, in fact, that I've spent the entire year dreading the two weeks of equine. You hear more gossip about it every few weeks, about students who had to do hourly checks all night and then were not allowed to go home the next morning. People who brought sleeping bags and camped out in the equine barn, or who got stuck with the 2-4am shift on a colicking horse. It's not just the dreaded "on call," it's the fact that it's also freaking horses. They can kill you, you know. They have killed vet students.

I arrived nice and early on the first day of equine, at the brand new equine barn up on the hill--it was only completed a few months ago and I'd never, ever been up there. I had no idea how to get in since the door was locked and not a single person was around, but fortunately my roster-mate showed up and we found a side door. Eventually, everyone else showed up, but it didn't really breathe life into the place. We got given a tour of the barn: a cold, high-ceilinged, mostly gray building (inside and out) with a lot of empty space.

After the tour we had rounds, where the previous weeks' students handed the cases over and the clinicians told us what new cases would be coming in. There were two that day, one of which was a horse coming in for laryngeal tie-back surgery.

The thoughts that went through my head went something like this: The larynx is interesting. Dogs get laryngeal paralysis, too, and it's also treated by laryngeal tie-back. If I wait, I may end up with a really unpleasant case, like a lameness. I should jump on it now since I'm kind of interested in it.

That's how I ended up volunteering to be the primary student on what turned out to be the most involved case of equine roster.

The horse was actually coming in for a second surgery, as the first one had failed. This one was going to be similar with a few tweaks to hopefully give it a better chance of success. Long story short, the second surgery failed, too. Very bad news for the owner, who was training this horse to be a racehorse. I had to learn all about the first surgery, the complications and chances of failure, the second surgery and it's complications and chances of failure, and the options--which included a third surgery, and it's complications and chances of failure. I had the pleasure of getting grilled about these things at every morning and evening rounds for an entire week.

It didn't help that the horse was a nightmare half the time. As far as horses go, I can imagine much worse, and I was at least able to get things done most of the time. However, there was a lot of head tossing and leg stomping and general uncooperativeness. She needed eye medication for a few days, and that was pretty much impossible. You would not believe how tightly they can clamp their eyelids together.

Probably the event that most showcased just how much that horse did not respect me was one time when I was trying to clean out a back hoof, and she simply would not lift it up. I pulled, I pushed, I yanked, I tried every trick in the book and had two people helping me, but she wouldn't budge. I finally gave up and switched with my more horse-inclined classmate, and two seconds later the job was done.

She finally went home after a week, without getting the third surgery. I managed to knock out a whole bunch of skills with the one case alone: physical exam, rebreathing exam, PCV/TP, faecal egg count, ophthalmic exam, general horse handling and grooming, sedation and IV injections, IV catheter placement, oral medication, intramuscular injections, scrubbing into surgery, and probably more than that. And since I had been up to my ears in research all week, I managed to write a pretty good case report on it.

I arrived nice and early on the first day of equine, at the brand new equine barn up on the hill--it was only completed a few months ago and I'd never, ever been up there. I had no idea how to get in since the door was locked and not a single person was around, but fortunately my roster-mate showed up and we found a side door. Eventually, everyone else showed up, but it didn't really breathe life into the place. We got given a tour of the barn: a cold, high-ceilinged, mostly gray building (inside and out) with a lot of empty space.

After the tour we had rounds, where the previous weeks' students handed the cases over and the clinicians told us what new cases would be coming in. There were two that day, one of which was a horse coming in for laryngeal tie-back surgery.

The thoughts that went through my head went something like this: The larynx is interesting. Dogs get laryngeal paralysis, too, and it's also treated by laryngeal tie-back. If I wait, I may end up with a really unpleasant case, like a lameness. I should jump on it now since I'm kind of interested in it.

That's how I ended up volunteering to be the primary student on what turned out to be the most involved case of equine roster.

The horse was actually coming in for a second surgery, as the first one had failed. This one was going to be similar with a few tweaks to hopefully give it a better chance of success. Long story short, the second surgery failed, too. Very bad news for the owner, who was training this horse to be a racehorse. I had to learn all about the first surgery, the complications and chances of failure, the second surgery and it's complications and chances of failure, and the options--which included a third surgery, and it's complications and chances of failure. I had the pleasure of getting grilled about these things at every morning and evening rounds for an entire week.

It didn't help that the horse was a nightmare half the time. As far as horses go, I can imagine much worse, and I was at least able to get things done most of the time. However, there was a lot of head tossing and leg stomping and general uncooperativeness. She needed eye medication for a few days, and that was pretty much impossible. You would not believe how tightly they can clamp their eyelids together.

Probably the event that most showcased just how much that horse did not respect me was one time when I was trying to clean out a back hoof, and she simply would not lift it up. I pulled, I pushed, I yanked, I tried every trick in the book and had two people helping me, but she wouldn't budge. I finally gave up and switched with my more horse-inclined classmate, and two seconds later the job was done.

She finally went home after a week, without getting the third surgery. I managed to knock out a whole bunch of skills with the one case alone: physical exam, rebreathing exam, PCV/TP, faecal egg count, ophthalmic exam, general horse handling and grooming, sedation and IV injections, IV catheter placement, oral medication, intramuscular injections, scrubbing into surgery, and probably more than that. And since I had been up to my ears in research all week, I managed to write a pretty good case report on it.

Thursday, 21 August 2014

Horse Dancing is a Thing

I had a vague understanding that dressage is a thing, but I never realised that they sometimes do it to music.

This interview by Stephen Colbert basically sums up the conversation we had this afternoon during some downtime on equine roster.

This interview by Stephen Colbert basically sums up the conversation we had this afternoon during some downtime on equine roster.

Tuesday, 19 August 2014

Horse Anaesthetic Equipment Is Giant-Sized

The title says it all. I scrubbed in on the surgery for my equine case, and as much as I don't like equine surgery, I have to admit, the stuff is pretty cool.

The surgery room itself is big and white and clean feeling, with windows for people outside to look in. It's attached to the recovery box, which is a big black room, and once the horse is induced, they lift it up using a stretcher thingy with giant chains attached to the really high ceiling. The whole wall of the recovery box opens up into surgery, and there's an invisible boundary between the two since surgery is sterile, so a sterile team waits on the other side to take over from the non-sterile team in the recovery box. The horse gets hoisted up, floated around a corner, and set down on the giant surgery table.

The anaesthetic circuit is basically the same as any other circuit, but it's giant-sized. The tubes are as big around as your arm. The ventilator is this giant cylinder. The rebreathing bag is as big as a pillow.

As you might imagine, the fact that horses are so big works against them. If they're on their back, all their organs press against their diaphragm and make it hard to breathe. Their own weight squashes their nerves and muscles and can ruin them if you don't take proper precautions. And that's just the tip of the iceberg of the headache that is equine anaesthesia and surgery.

The surgery room itself is big and white and clean feeling, with windows for people outside to look in. It's attached to the recovery box, which is a big black room, and once the horse is induced, they lift it up using a stretcher thingy with giant chains attached to the really high ceiling. The whole wall of the recovery box opens up into surgery, and there's an invisible boundary between the two since surgery is sterile, so a sterile team waits on the other side to take over from the non-sterile team in the recovery box. The horse gets hoisted up, floated around a corner, and set down on the giant surgery table.

The anaesthetic circuit is basically the same as any other circuit, but it's giant-sized. The tubes are as big around as your arm. The ventilator is this giant cylinder. The rebreathing bag is as big as a pillow.

As you might imagine, the fact that horses are so big works against them. If they're on their back, all their organs press against their diaphragm and make it hard to breathe. Their own weight squashes their nerves and muscles and can ruin them if you don't take proper precautions. And that's just the tip of the iceberg of the headache that is equine anaesthesia and surgery.

Friday, 8 August 2014

Turtle Lamp

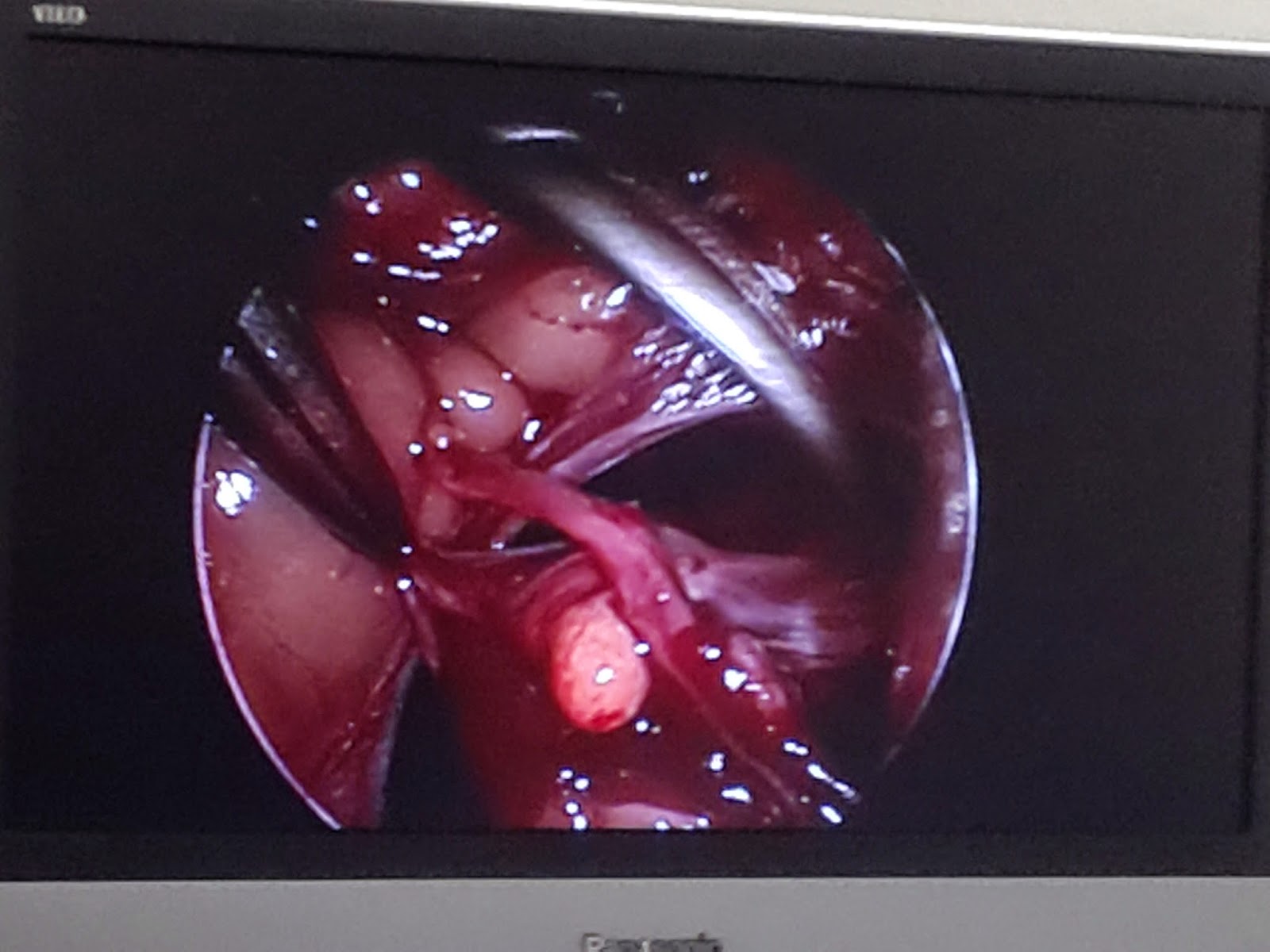

You might be wondering how surgeons get inside the turtle. It turns out that one of the methods is to make an incision in the soft area in front of their back legs (or front, depending on what you want to do). Then they can stick an endoscope in, with a light source and a camera on it, and use tiny instruments with long handles. The best part is that the light makes the internal cavity of the turtle glow, and you can see it through the shell on their belly!

I can't find any good photos on google, so I'm going to show you the ones I took. I'm not sure if we're allowed to do that, so uh, don't tell the school on me please.

Intubated and with an IV catheter in her jugular.

The reason the turtle looks so yellow is because there's a sticky sterile covering with iodine in it, called Ioban.

If you look carefully, you can see how bright the pink inside of the turtle is because of the light from the endoscope.

The screen showing the instruments and tissues on the endoscope.

Why was this turtle having surgery? The short and simple version is that it had egg impaction. And how did they definitively diagnose that? A CT scan. In case you were wondering, here's a picture from google of a turtle CT scan:

Thursday, 7 August 2014

We Killed A Dinosaur

Wildlife medicine in New Zealand is somewhat unique. There are a lot of critters here that don't exist anywhere else, and, conversely, things that aren't here that are everywhere else. During my time on wildbase, I sadly never got to see a snake or ferret. But I did get to see lots of super endangered native creatures, such as takahe. There's like 260 of them left.

And tuatara, which are basically dinosaurs, and the star of today's blog post.

They're basically prehistoric. They're so primitive, they're their own order. I know they look like lizards, but they're closer to dinosaurs. According to wikipedia, "The two species of tuatara are the only surviving members of their order, which flourished around 200 million years ago."

One of them came to the hospital with a diseased eye. It had probably been traumatised (eg poked it into a stick or something) and was now blind, or at least that's my understanding. All their heroic efforts to treat it medically had failed, so it came down to surgery. The first eye enucleation surgery to ever be performed in a tuatara.

The interesting thing about wildlife and exotic medicine is that there isn't a whole mountain of literature for every single species. You might be the second person ever to anaesthetise a giraffe with that combination of drugs, so all you have to go on is one twenty-year old case report and extrapolation from other species. Unfortunately that's not as easy as it sounds, because drugs can have dramatically different effects as species have small differences in enzymes or receptors or whatever. For instance, cats are massively different to dogs in some areas, and we have lots of research about those species. You can imagine how often we diagnose and treat the same disease in, say, a tiger. Now imagine how likely you are to find anything published about a species that numbers in the thousands.

The other fun thing about tuatara surgery is that reptiles are ridiculous animals. The way it was explained to me is that everything in birds happens super fast, they can turn on a dime, and everything that happens in reptiles happens super slow. If a reptile emergency comes in, the first thing you should do is put on the kettle, so you can have a think about it over your tea. Any changes in their health tend to take a long time to manifest. That is important information for this story.

We went ahead with the surgery, which was all quite exciting. It was especially exciting for anaesthesia, who were very stressed out. I don't remember the details because I wasn't on anaesthesia then, but things like heart rate and respiratory rate were apparently quite distressing. So while anaesthesia was freaking out, the wildlife clinician was calmly shrugging it off, with the explanation that some crocodillians can have heart rates as low as one beat per minute. Turtle hearts can keep beating for 24 hours after death (as in, when you open them up at necropsy, you can find their heart beating in front of you... even if you take it out, apparently). Basically, it's impossible to tell if they're dead or alive while under anaesthesia, so he decided not to worry about it. (It fits the theme of not being able to tell if animals are alive while on wildlife roster).

The surgery went along just fine. They packed the empty eye socket with some mini absorbable sponge thingies and sutured it all up. They made it a little bandage that made it look like a pirate. I have an adorable picture, but I doubt I'm supposed to share it on the internet (it might get picked up by google images or something and be stuck there forever when people search about tuatara, and then I think the university might get a teeny bit mad at me).

Details aside, things were fine and dandy that night and into the next morning. During the day, however, the tuatara slowed down, and in grand reptile fashion, we began to question whether it was alive or not. The clinicians broke out more heroics and it went under intensive care for most of the afternoon. Interestingly, since tuatara are in their own order, you need another tuatara if you want to do a blood transfusion... and there's not too many of them around, as you can imagine.

We had the little guy on oxygen, breathing for him, and all sorts of monitoring. He got drugs and fluids and blood products and heating pads and everything we could think of. Unfortunately the monitoring equipment isn't exactly built for tuatara, so the accuracy was questionable, making it even harder to tell anything about the heart or whatever. The heart rate went down and he wouldn't breathe for himself. We did what we could, and gave it a few hours for good measure. He had gone very pale. Surprisingly, we still couldn't figure out if he was actually dead, so we stopped breathing for him and let the chips fall as they may. We put him back in the incubator for the night, just to be sure. The next morinng he hadn't moved any, so we were getting pretty confident we'd lost him.

Too bad for the world's first enucleation on a tuatara. The upside of taking two days to die is that we'd all kind of... accepted it. By the time we gave up on him, I had plenty of time to prepare myself emotionally so I wasn't particularly upset. If he'd given up the ghost in the middle of surgery or something, that would have been more difficult to deal with.

And tuatara, which are basically dinosaurs, and the star of today's blog post.

They're basically prehistoric. They're so primitive, they're their own order. I know they look like lizards, but they're closer to dinosaurs. According to wikipedia, "The two species of tuatara are the only surviving members of their order, which flourished around 200 million years ago."

One of them came to the hospital with a diseased eye. It had probably been traumatised (eg poked it into a stick or something) and was now blind, or at least that's my understanding. All their heroic efforts to treat it medically had failed, so it came down to surgery. The first eye enucleation surgery to ever be performed in a tuatara.

The interesting thing about wildlife and exotic medicine is that there isn't a whole mountain of literature for every single species. You might be the second person ever to anaesthetise a giraffe with that combination of drugs, so all you have to go on is one twenty-year old case report and extrapolation from other species. Unfortunately that's not as easy as it sounds, because drugs can have dramatically different effects as species have small differences in enzymes or receptors or whatever. For instance, cats are massively different to dogs in some areas, and we have lots of research about those species. You can imagine how often we diagnose and treat the same disease in, say, a tiger. Now imagine how likely you are to find anything published about a species that numbers in the thousands.

The other fun thing about tuatara surgery is that reptiles are ridiculous animals. The way it was explained to me is that everything in birds happens super fast, they can turn on a dime, and everything that happens in reptiles happens super slow. If a reptile emergency comes in, the first thing you should do is put on the kettle, so you can have a think about it over your tea. Any changes in their health tend to take a long time to manifest. That is important information for this story.

We went ahead with the surgery, which was all quite exciting. It was especially exciting for anaesthesia, who were very stressed out. I don't remember the details because I wasn't on anaesthesia then, but things like heart rate and respiratory rate were apparently quite distressing. So while anaesthesia was freaking out, the wildlife clinician was calmly shrugging it off, with the explanation that some crocodillians can have heart rates as low as one beat per minute. Turtle hearts can keep beating for 24 hours after death (as in, when you open them up at necropsy, you can find their heart beating in front of you... even if you take it out, apparently). Basically, it's impossible to tell if they're dead or alive while under anaesthesia, so he decided not to worry about it. (It fits the theme of not being able to tell if animals are alive while on wildlife roster).

The surgery went along just fine. They packed the empty eye socket with some mini absorbable sponge thingies and sutured it all up. They made it a little bandage that made it look like a pirate. I have an adorable picture, but I doubt I'm supposed to share it on the internet (it might get picked up by google images or something and be stuck there forever when people search about tuatara, and then I think the university might get a teeny bit mad at me).

Details aside, things were fine and dandy that night and into the next morning. During the day, however, the tuatara slowed down, and in grand reptile fashion, we began to question whether it was alive or not. The clinicians broke out more heroics and it went under intensive care for most of the afternoon. Interestingly, since tuatara are in their own order, you need another tuatara if you want to do a blood transfusion... and there's not too many of them around, as you can imagine.

We had the little guy on oxygen, breathing for him, and all sorts of monitoring. He got drugs and fluids and blood products and heating pads and everything we could think of. Unfortunately the monitoring equipment isn't exactly built for tuatara, so the accuracy was questionable, making it even harder to tell anything about the heart or whatever. The heart rate went down and he wouldn't breathe for himself. We did what we could, and gave it a few hours for good measure. He had gone very pale. Surprisingly, we still couldn't figure out if he was actually dead, so we stopped breathing for him and let the chips fall as they may. We put him back in the incubator for the night, just to be sure. The next morinng he hadn't moved any, so we were getting pretty confident we'd lost him.

Too bad for the world's first enucleation on a tuatara. The upside of taking two days to die is that we'd all kind of... accepted it. By the time we gave up on him, I had plenty of time to prepare myself emotionally so I wasn't particularly upset. If he'd given up the ghost in the middle of surgery or something, that would have been more difficult to deal with.

Monday, 4 August 2014

Phew, He's Breathing / Classic Vet Student Moment

A very sick little blue penguin was brought to the hospital. It wasn't doing well, so it went straight into what's basically the ICU "tank" in the wildlife ward, a clear incubator/oxygen cage thingy.

When I came back from lunch, the poor guy looked awfully still. I watched him for a moment, then had a mini panic attack when I couldn't see him breathing.

Deeply concerned, I peered into the tank and watched him for a good minute. Uh oh, did he stop breathing? Do we need to start CPR? Then, much to my relief, I thought I saw some chest movement. Phew! He's breathing.

The clinician came out of the ward a moment later and said, "The little blue penguin died while you were at lunch, by the way."

When I came back from lunch, the poor guy looked awfully still. I watched him for a moment, then had a mini panic attack when I couldn't see him breathing.

Deeply concerned, I peered into the tank and watched him for a good minute. Uh oh, did he stop breathing? Do we need to start CPR? Then, much to my relief, I thought I saw some chest movement. Phew! He's breathing.

The clinician came out of the ward a moment later and said, "The little blue penguin died while you were at lunch, by the way."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)