The day started with a bang and never slowed down. On account of being a monday, after a brief tour, I got thrown into the whirlwind of getting food and meds to all 20-odd patients, with only the most basic experience to go on. After cutting up fruits, veggies, and almonds, my first animal-related task was to hold a kiwi while the vet tech force fed it. That's right, a kiwi.

One of the patients is a Kaka.

Mondays are apparently particularly hectic because they have rounds on mondays and thursdays. Treatments had to be finished by nine, and then all the wildlife staff (less than ten people) gathered around the tiny clinic to go over the history, diagnostic findings, and treatments for all the patients. There are a number of birds with wing or leg fractures that got surgery, with pins and external fixators and the whole kit and kaboodle. There are a few skinny birds that have been losing weight, a few odds and sods like strange skin lesions or neuro. One bird is in for diagnostics to confirm diabetes insipidus. At the other location, near the large animal teaching unit, there are purportedly three penguins and a few other big birds, but I didn't get out there today. One of the patients is an endangered New Zealand bird, and there are only around 400 left in the world.

After rounds, we had radiology booked for the morning, as we had three birds to radiograph. A harrier, a kingfisher, and some sort of pigeon. Wildbase is great because they have students every week and plunge you right into it. Almost right away, I was positioning the animals, holding, taking blood, making blood smears (badly), running PCV/TP, palpating lesions, all sorts of stuff.

A harrier.

After lunch, there were two consults. One was a sulfur crested cockatoo who we admitted for a whole slew of diagnostics, including bloodwork and skin scrapes. The other, however, made my day. It was a pet turtle with conjunctivitis, secondary to vitamin A deficiency (quite a common deficiency in exotic pets). So we did an ophthalmic exam on this turtle. I got to hold it while we examined and treated this turtle, and turtles are exactly as cute and awesome as you'd expect them to be (as long as you don't get bitten). Its little legs waggled around as I sandwiched it between my palms.

Ours was larger, but looked basically the same.

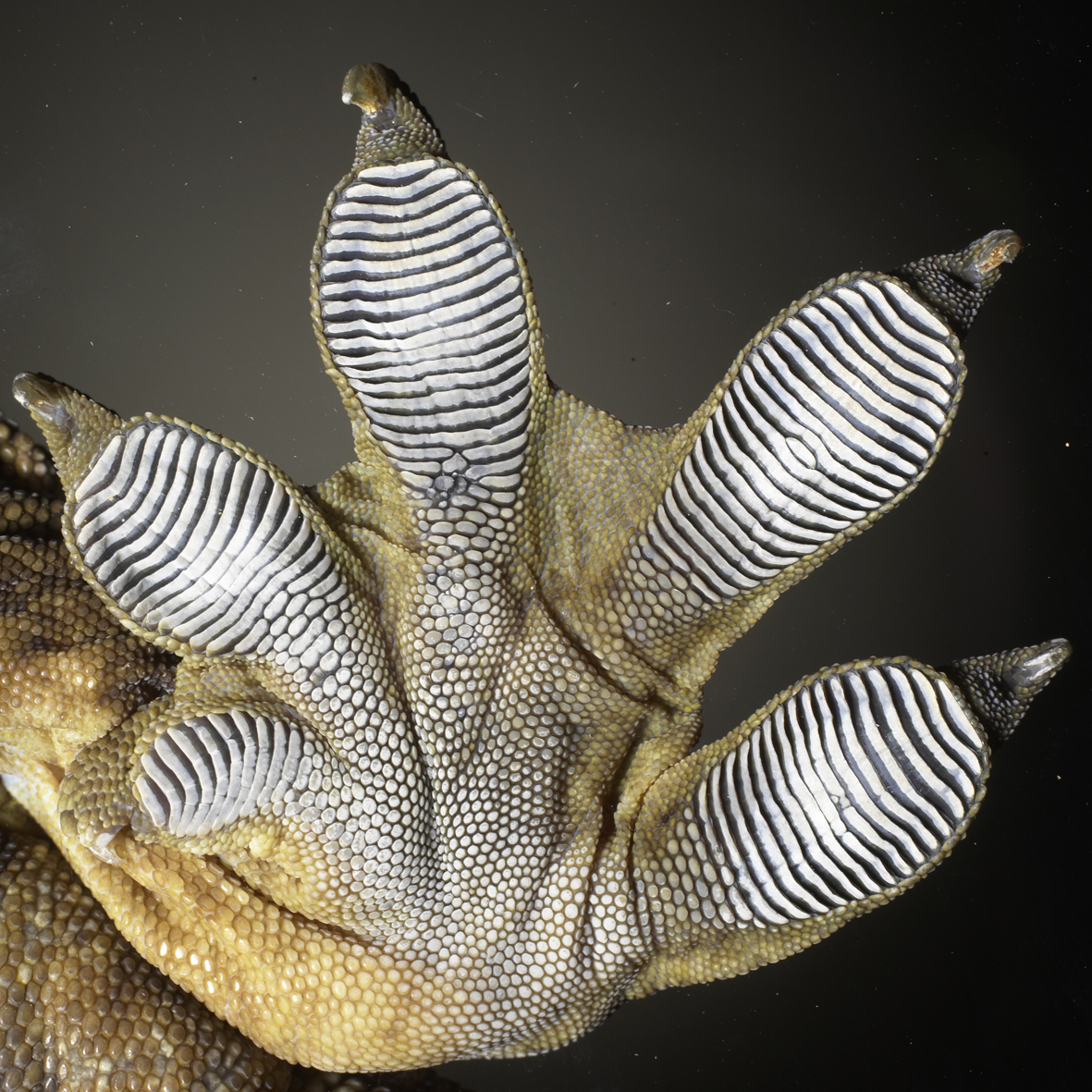

After the consults, it was time for the gecko surgery. Yeah, gecko surgery. It had a mass on its neck that was removed. Anaesthetists joined us to manage the anaesthesia, and the whole process of induction and intubation was quite an undertaking. The gecko was on a mask, and when it was asleep enough to lose its "righting reflex" when flipped over, they tried to get the endotracheal tube in. However, the gas anaesthetic diffuses out of the lungs pretty quickly, so there was a limited amount of time for each attempt. Because of the unusual anatomy, it took many attempts.

Despite all that, overall, the procedure wasn't much different than it would be for any other animal. The concerns about respiration and blood pressure are basically the same, it's just a tiny-sized animal. Surgical technique is the same. Suturing is the same, it's just scaly reptilian skin instead. Though, there are a lot of quirks to bear in mind as well. For instance, turtles' lungs are attached to the dorsal carapace, so if you need to ventilate them, you can flap their legs back and forth, and it actually works the lungs!

I also learned that the bottoms of geckos' feet are really, really cool. Not only do they look neat, they feel pretty neat, too.

More surgeries and radiographs and anaesthetics on the schedule for tomorrow, with all sorts of native New Zealand birds. Should be pretty exciting!

No comments:

Post a Comment